The Big Picture in International Taxes

There used to be a clearer picture of what the problems were in the global tax system. But today, we're still struggling to evaluate whether the solutions we've implemented are working.

This newsletter, you may have noticed, is unapologetically in-the-weeds. Or at least, it is when compared to general audience news writing about taxes. It’s for folks who like (or need) to dive into the details and nuances of international taxation, written by someone who’s become obsessed with the topic after covering it for more than 10 years.

Tax wonks and practitioners often get criticized for letting the details consume them, for losing sight of the big picture, the forest in the trees. As someone whose career started in local newspapers, I’ve been trained to constantly ask myself, “Why does this matter? How does it affect normal people? Why is it worth a reader’s time?” I think this instinct has helped me write about taxes, but I too will get lost in the details and wonkery.

Sometimes, it does help to take a second and contemplate the big-picture view. What is the international tax system trying to do? What is the moral responsibility of those in an economy to contribute to the governments that make it possible? And why are those contributions important–what do they fund?

The trouble is, right now the big picture is fuzzy.

When I started this in 2012, there was more or less agreement on what the big problems were in international taxes. The rules were outdated, new business models relied heavily on intangible assets for income, and this mobile income was easily moved to jurisdictions with low tax rates. Sometimes, it's difficult to pinpoint where the income should have been sourced in the first place, especially when the underlying activity happens mostly online. U.S. rules allowed companies to defer offshore income from repatriation, avoiding trillions in taxes while still using the earnings to boost share prices. They could even invert out of the U.S. to avoid taxes on repatriated income forever. The incentives were perverse and no one would have ever designed a system this way. When corporations pay less than what would seem to be fair, it’s not only a problem for revenue–it undermines public faith in the system and breaks the implicit mutual promise of taxation.

Everyone pretty much agreed on this, even if they varied wildly on solutions.

All of these elements are still present today. But what’s changed is that several initiatives at home and abroad have finally attempted to tackle these issues. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s 2015 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting project, predating its current “Two-Pillar Solution,” came up with new rules to evaluate intangibles, in theory dealing with on-paper profit allocation to havens. They also created new reporting requirements which would make it much easier for tax authorities to pinpoint where the havens were–and make taxpayers more reluctant to use them.

In 2017, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act finally repatriated all of that offshore cash–at a steep discount–and created new rules to target low-taxed offshore income. The tax on global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI) and the base erosion and anti-abuse tax (BEAT) both put common tax avoidance structures in their sights. Much of the rest of the world followed suit, and these elements became part of the OECD’s current plan, which–despite many hiccups–is likely going to become part of the global tax landscape, one way or another.

And then there’s the new corporate alternative minimum tax, (CAMT or “cam-tee” for the wonks), meant to hit corporations with low effective tax rates. Whether it will really curb offshore profit-shifting–or if there’s even much shifting to curb–is hotly debated by experts. But it's yet another rule meant to hit low-taxed income.

In between the lines of all this, you have a soft enforcement dynamic that may have just as big an impact. Tax avoidance can be maddeningly hard to define, but like pornography, you know it when you see it. When countries craft laws to try to stamp out certain types of behavior, even when they’re imperfect, the offending actors sometimes get the picture and stop anyway. The subjectivity of the international system works both ways–it makes it easier for companies to manipulate the rules but it also lets countries use aggressive auditing to get the result they want.

One example: Amazon was heavily criticized for operating in countries without creating a taxable presence, because warehousing and distribution were considered auxiliary in most tax treaties. During the OECD BEPS project, negotiators painstakingly refined the model treaty language to try to capture this. The U.S. insisted that this new provision be optional. They ultimately settled on a new passage which arguably fixed the issue but could have been a nightmare in enforcement.

But no matter–Amazon had restructured itself well before any of that worked its way into law.

For most people, who see occasional media coverage about nefarious foreign tax havens, it seems like the problem has been allowed to fester for years. But in fact, efforts to design and implement solutions to these problems are, pretty much, all I’ve written about over the past decade. This isn’t a case of Americans being ignoramuses–most highly educated and informed people have never heard of the OECD or GILTI.

So are these initiatives working? The unsatisfying answer is, we don’t really know.

The amount of profit-shifting is notoriously difficult to pin down, and academics aren’t even really sure how to define it. Most of these reforms are only a few years old–and some of those years, you may recall, were highly unusual. There’s individual data points and anecdotal evidence you can cherrypick–yes, many of the tech giants did repatriate their IP after the TCJA took effect. Yes, many companies have continued to keep income offshore. But they don't add up to a clear picture.

What I’ve heard from practitioners is that many companies are still wary of totally unwinding their offshore tax structures, even now. So while the profits may still be piling up offshore, that doesn’t mean they’re actively being shifted–the taxpayers is choosing to take the hit in GILTI taxes and other disincentives. The real test will be when a new generation of valuable IP comes along–will companies set up new cost-sharing arrangements to move those intangibles offshore? Many think they won’t. (By “next generation,” I’m not talking about the next iPhone or Droid operating system. Those patents are typically generated offshore in the first place, that’s the point of a cost-sharing structure. I mean the new programs, brands and patents that we couldn’t even think of today.)

Democrats, of course, have been highly critical of the TCJA and tend to scoff at the idea that it's done anything to reduce tax avoidance. They note that GILTI still allows some profit-shifting through global blending, and they claim the 10.5% rate is too low. Maybe they're right. But there's an element of dogma in their talking points on this--because GILTI's ineffectiveness is central to their critique of the TCJA's international framework, it must be flawed, regardless of what the evidence says.

There's also resistance to seeing the TCJA as a complex law which will take time for the full effects to be seen. It's often called the "Trump tax cuts," as if it took hundreds of pages to replace "35%" with "21%." It's not seen as a policy with many moving parts and the nuanced balancing of incentives--like the Affordable Care Act, which supporters said couldn't be evaluated until years after its enactment. Even though it's more than 5 years old, the law's full scope isn't clear.

Whether GILTI or the new OECD proposals, most of these rules serve to backstop the existing system, creating disincentives through formulaic proxies for the outcomes we’re hoping to stop, so that hopefully the entire system won’t have as much strain. You could say–and many do–that this doesn’t confront the fundamental problems with how we source and allocate taxable income. But that doesn’t mean that the solutions won’t work on their own terms.

I should note that this is my opinion and interpretation–many disagree. But if the evidence was compelling one way or another, there’d be more of a consensus. And there’s plenty of debate about what an ideal system would look like–should it have less competition, more destination-based taxation, or an entirely different framework? But these issues, while interesting, don’t lend themselves to the compelling overall narrative that once drove the international tax discussion.

Don’t get me wrong–the international tax system is in a state of profound chaos right now. The rules are constantly changing and evolving, and many are wondering if the fundamental cornerstones put in place 100 years ago will withstand. And the global economy continues to transform and create new business models that flummox the traditional tax rules.

Once all the dust settles–if it ever does–we may see a return to substance-free tax havens, just like before. Or maybe, some entirely new form of tax arbitrage we couldn't think of today will become the most important thing in the tax world.

In the meantime, this transitionary period will be more than enough to keep us international tax wonks employed and occupied for the foreseeable future.

DISCLAIMER: These views are the author's own, and do not reflect those of his current employer or any of its clients. Alex Parker is not an attorney or accountant, and none of this should be construed as tax advice.

LITTLE CAESARS: NEWS BITES FROM THE PAST WEEK

- Government officials are beginning to say out loud what everybody knows–Pillar One of the OECD’s Two-Pillar project, meant to replace national digital services taxes, faces long odds of ever coming to fruition. Most recently it was Bruno Le Maire, France’s finance minister, who has been an outspoken figure in this process since the beginning. Speaking before the G-20 Finance Ministers’ meeting, Le Maire said that “the chances of success seem slim” for Pillar One, and the European Union needs to move forward with its own digital tax. France was one of the most prominent countries to enact its own digital tax (remember Trump’s threat to tax French wine?) so this is hardly a surprise–but Le Maire’s comments could serve as a reminder to everyone that the alternative to Pillar One is not the status quo.

- South Africa is the latest country to move to enact the 15% global minimum tax into its national laws, calling for it to be enacted into law in its 2023 budget. This is yet more evidence of the policy’s momentum despite the U.S. resistance.

- The U.S. Treasury Department issued another piece of interim guidance regarding the corporate alternative minimum tax, this time dealing with potential distortions in how the tax would treat life insurance. This likely only affects a sliver of companies, but shows that the department has begun getting into the nitty-gritty of how CAMT will affect particular industries and transactions.

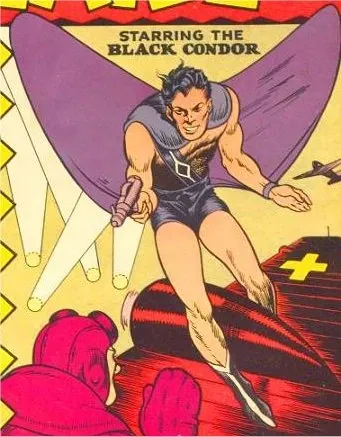

PUBLIC DOMAIN SUPERHERO OF THE WEEK

Black Condor, who premiered in Crack Comics #1 in 1940. An orphaned son of archaeologists who learned how to fly after being raised by giant condors in….Mongolia? (He was eventually absorbed into the DC Universe, and this fantastic backstory was dropped.)

Contact the author at amparkerdc@gmail.com.