The Book Min Tax and the Return to Worldwide Taxation

The corporate book minimum tax may be setting the U.S. back onto a course of worldwide taxation. It's worth talking about what that means.

In Ernest Hemingway’s classic novella “The Old Man and the Sea,” a fisherman harpoons a giant marlin, too big to fit into his boat. As he drags the fish back to shore, sharks take out bite after bite, until he’s left with nothing but the head and the skeleton.

The 15% corporate book minimum tax, a centerpiece of the soon-to-be-passed Inflation Reduction Act, isn’t quite that disfigured. But to get the legislation across the finish line, Senate Democrats were forced to add yet another exemption to a tax which was already riddled with exceptions and adjustments. Sen. Krysten Sinema (D-Ariz.) wouldn’t agree to a yes vote unless the tax accounted for accelerated depreciation–one of the biggest causes of divergences from taxable income and profit as measured by the "book" financial accounting used for public filings.

This is after the legislation already carved out many tax incentives such as those for green energy, low-income housing, and research & development–the latter being another major cause for the low effective tax rates. The book minimum tax is supposed to apply when a company's tax payments are too low, compared to its book income (rather than its taxable income), but the law exempted so many of the reasons why that normally happens.

What remains may not be a skeleton–it’s still the biggest revenue-raiser in the bill, according to the Joint Committee on Taxation. But it’s far from the majestic, sleek marlin that Democrats had hoped they had hooked.

If it’s not reversing timing differences or clawing back the major incentives leading to low effective tax rates, what is it doing? What’s the primary purpose of this weird tax? Just what the hell is it?

One answer is that it’s a tax on companies which use stock-based compensation, one of the biggest remaining causes for book-tax disparities. It catches some other remaining timing differences, such as the different schedule for the amortization of goodwill. But a big item on the list is low-taxed foreign income, earned in jurisdictions with tax rates lower than the U.S. 21% corporate tax rate.

In fact, I think one of the most important attributes of the new book minimum tax is so simple and obvious, tax experts overlook it and its implications. The book min tax is a worldwide tax. It applies, potentially, to all income earned abroad by U.S. companies, no matter where it is earned or kept.

The U.S. took major strides towards creating a territorial tax system during the Trump administration, exempting huge chunks of international income from taxation. Now, the pendulum is swinging in the opposite direction, and this could end up becoming a significant dynamic between the U.S. and the rest of the world.

According to its supporters, the book min tax is supposed to target only companies that are not “paying their fair share,” using loopholes in the system to skirt their public responsibilities. President Joe Biden sometimes implied this was through the use of offshore tax havens. And indeed, many corporations list low foreign taxes as a reason why their effective tax rates are lower than the statutory 21% rate.

But foreign income isn’t necessarily profit that has been shifted to havens. Just as likely, it is income that’s been “naturally” earned overseas, from real facilities or sales there. And since the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act passed in 2017, it’s income that’s supposed to be untaxed by the U.S. That’s the key attribute of a territorial system, to focus only on taxing activity within your own borders, and let other countries worry about everything else. Even the foreign income of your own taxpayers.

Unlike the TCJA’s anti-abuse rules, such as the tax on global intangible low-taxed income, the book minimum tax doesn’t have a formula to determine “good” or “bad” foreign income. It doesn’t care whether it’s income stored in a haven’s post office box or earned through a thriving operation. It’s all added into the percentage either way.

And that’s the point–in this sense, it’s a pure, hard worldwide tax, a throwback to the days when the U.S. wanted a chunk of all income earned by its residents.

It was, sort of, sold that way.

In the years before the TCJA, there was something of a shaky bipartisan consensus for shifting to a territoriality. With the deferral of income making a mockery of the international tax code, a system which gave up the hopes of taxing income around the world, but did prevent U.S. income from eroding offshore, seemed vastly preferable. The TCJA did this, kind of. It exempted most foreign income of U.S. companies but enacted the GILTI tax, a new worldwide regime which has proven to be much broader than most taxpayers anticipated.

(To me, GILTI is still in keeping with the territorial concept, because however clumsily designed, it’s meant to target income which would be in the U.S. if not for profit-shifting. But I’ve yet to meet any tax expert who agrees with me on this, so I’m probably wrong.)

Like some rule of political gravity, whatever consensus for territoriality existed pre-2017 shattered after the TCJA’s passage, and Democrats almost uniformly called for a return to worldwide taxation. Almost all of the major 2020 Democratic contenders proposed stronger taxes on offshore income, and blamed the TCJA for encouraging not only income-shifting but job migration from the U.S.

It’s hard to blame them–territoriality is a very counterintuitive concept to those not steeped in tax policy. Why should the U.S. ever grant preferable tax treatment to activities in foreign countries, over those right here? The talking points and campaign ads practically write themselves.

Biden came into office promising to end incentives to ship income and jobs overseas, and while his (dropped) international tax provisions were the primary tool for this, the book minimum tax was also part of the package. It doesn't even really have anything to do with using "book" income, except that it chooses to look at worldwide financial profit.

The territorial/worldwide debate is actually hiding behind many of the current tax policy disputes. Democrats also claim that the exemption for qualified business asset investment–depreciable tangible property, how the GILTI tax determines what is intangible income–encourages offshoring by reducing the tax burden on job-producing operations in foreign countries. This must be an unintended loophole, Dems say–who could ever want to encourage job growth overseas? But actually, this is the whole idea with a territorial system. Ideally, the U.S. shouldn’t be taxing any of the income of U.S. taxpayers when it’s earned overseas, under a territorial paradigm. GILTI only exists because some profit tends to be associated with profit-shifting, when taxable income is separated from the economic activity that generates it.

Tax policy discussions can get dense and technical. But the 100-year-old debate on worldwide vs. territorial taxation (or its close sibling, source vs. residence) gets much more stark and philosophical. It’s about the very nature of taxation–who has the moral right to tax what commerce, and how should these competing rights be adjudicated?

At its simplest, the debate is about what makes for the sturdiest pillar of an international tax system–the residence of the taxpayer or the location of economic activity? Residence has been a useful determinant throughout the history of taxation, and maybe it still works today. But there’s something arbitrary and artificial about it, trying to apply a national label to corporations which are truly global in everything but name. And as remote work redefines the concept of the home office, it’s likely to seem more and more outdated by the minute.

Location of economic activity may be more tied to reality, or some version of it. But it’s also a highly complex and subjective determination, a challenge for even the most sophisticated tax authorities to administer. Will it ever become truly workable?

Residence-based, worldwide taxation seems appealing. It offers the hope of casting aside the cross-jurisdictional transactions and income-shifting that are so vexing to tax authorities. Ideally, it could make tax havens all but useless. If your home country taxes all of your income, it doesn’t matter where you put it. But there’s always a catch, and in this case it’s that pure worldwide taxation puts all of the weight of the international system on the definition of residence. Can that concept withstand the burden?

Perhaps it makes sense for the U.S., as the home of so many of the world’s largest and most successful companies, to lean on the residence concept more than other nations. It’s hard to imagine Apple or Google becoming foreign-parented corporations, no matter how strong the economic incentives driven by taxes. But you might have said the same about Chrysler and Anheuser-Busch in the 1960s. (Both iconic American brands are now foreign-owned.) The specter of inversions or foreign corporate takeovers looms large in a system that relies on home-based companies for its revenue, no matter how many rules are enacted to try and block them.

These are just a few of the issues in the great worldwide vs. territorial debate, that have been swirling in tax policy circles for more than a century. (To see some of the history, check out Michael Graetz’s fascinating 1997 paper on the first multilateral international tax agreements, “The ‘Original Intent’ of U.S. International Taxation.”)

Despite the seemingly stark divides, no country’s system is entirely worldwide or entirely territorial. It’s all on a spectrum. And with the book min tax, the U.S. is still largely territorial, at least in theory. The book min tax isn’t just a tax on foreign income, it mixes it in with income from many other sources to produce a single measurement–which may not be taxed at all, if it’s high enough.

But it could be a step in that direction, maybe the first of many as it sets new expectations about what should and shouldn’t be taxed. The rest of the world still operates largely on a territorial basis–even with the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s project to overhaul the system. We’re Americans, though, we do things in our own way. Those ways could set the stage for conflict in the years ahead.

DISCLAIMER: These views are the author's own, and do not reflect those of his current employer or any of its clients. Alex Parker is not an attorney or accountant, and none of this should be construed as tax advice.

OTHER NEWS OF THE WEEK

The African Tax Administration Forum released a statement August 3 following a Cross Border Taxation Technical Committee Meeting, in which it repeated concerns about the complexity and potential administrative burden of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development's Pillar 1 project. Developing countries have complained throughout the Pillar 1/2 process that their voices have been disregarded in negotiations, despite the 141-nation Inclusive Framework. Ultimately, all but a (not insignificant) handful signed onto the agreement. The ATAF has become one of the more pivotal groups representing non-Western countries in tax matters. Albeit, they focus more on administrative issues than policy ones--but it's interesting to see those roles converge here. Whatever they say is always worth paying attention to.

The IRS has kicked up a whirlwind in its case against famed home appliance manufacturer Whirlpool Corp., which could be headed to the Supreme Court. The National Association of Manufacturers, PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP, Deloitte Tax LLP, KPMG LLP, the Silicon Valley Tax Directors Group and the National Foreign Trade Council, among others, all filed amicus briefs in support of the Michigan-based company, in the case Whirlpool Financial Corp. & Consolidated Subsidiaries et. al. v. Commissioner of the Internal Revenue Service. This is a complex, very technical case with huge potential consequences for multinational manufacturers, which also involves one of my favorite tax words, the maquiladora. (Foreign corps that use a Mexican tax incentive to manufacture exports in designated areas without duties, tariffs or taxes.) PwC had an interesting podcast about this case back in March.

Australia and Canada both issued consultation papers on tax anti-abuse issues in the past week, a reminder that Western countries aren’t waiting for the OECD project to finish before tackling what they see as complex arrangements designed to circumvent the tax law. Australia’s paper deals with interest deduction limitations, intangibles arrangements, and tax transparency, while Canada is proposing to sharpen its General Anti-Avoidance Rule.

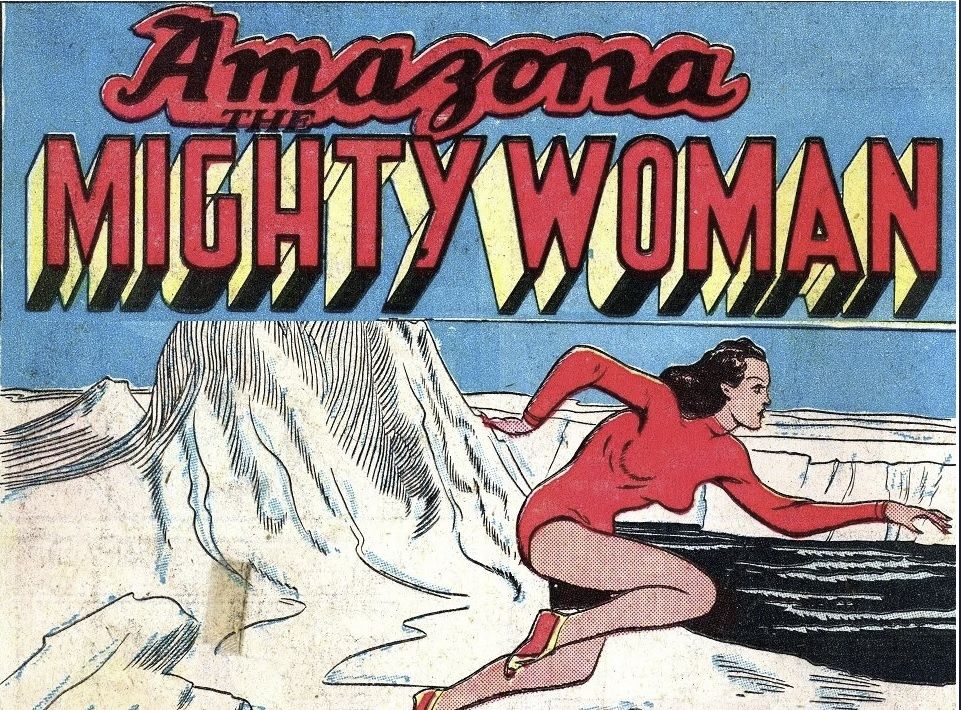

PUBLIC DOMAIN SUPERHERO OF THE WEEK

Amazona: the Mighty Woman, created by Wilson Locke, Alex Blum, and Dan Zolnerowich for Planet Comics #3 in 1940. One of the last descendants of a “super-race” that nearly died out during the Ice Age, she lived in frigid peace in the Arctic before an American explorer brought her back to the U.S., where she became tangled in plots with gangsters. She only appeared in one issue. Believe it or not, this was one year before the similarly-themed Wonder Woman would debut and change comics forever.