The Potentially Insurmountable Hurdles to Wealth Taxation in America

International tax transparency may make a wealth tax more feasible today than in the past. But in the U.S., the concept faces political and legal challenges that could prove fatal.

Wealth taxes are back in the news, somewhat, as blue-leaning states are looking to pick up where Congress has, so far, neglected to go. The so-called laboratories of democracy may be ideal venues to try this idea, but they’ll also likely have to deal with the same issues that led to the policy’s failure in Europe. Why would billionaires choose to live in a state that threatens to reduce their wealth significantly, and could any state have enough leverage to try to capture the assets of fleeing high-net-worth residents?

Likely, a wealth tax is going to need to be implemented at the federal level if it has any chance of sticking and truly affecting revenues and economic inequality. But as critics have been quick to point out, it faces potentially insurmountable challenges at the federal level too.

It’s worth examining those challenges a bit more, however. The specter of Europe’s failed taxes looms large over the debate, especially the prospect of wealth (and the wealthy) fleeing the U.S. rather than submitting to the tax. In addition, there are the challenges with valuation, which the Internal Revenue Service also faces with regard to the estate tax and capital gains. And then there’s the constitutional question–would wealth tax backers need to pass an amendment, just as income tax supporters did more than a century ago?

But it’s not the 1910s or the 1990s. From the time I’ve spent covering this issue, I’m convinced that the fears of evasion and asset migration are likely overblown–but the constitutional challenges are likely underappreciated.

It could well be that a wealth tax is both legally and politically impossible. But if it were somehow enacted, its implementation could be easier than many imagine, in a new interconnected and transparent world where there are fewer and fewer places to hide.

Europe’s once-ubiquitous wealth taxes fizzled in part because it gave the wealthiest an overwhelming incentive to move–and the only somewhat wealthy, with less in liquid cash to pay the tax, were left with the bill.

On this side of the Atlantic, the United States has always taxed the worldwide income of its citizens, since the beginning of the income tax. Those bold enough to renounce their citizenship, such as Facebook co-founder Eduardo Saverin, can escape future taxes. But there’s no reason, in principle, that the U.S. couldn’t charge an exit tax on existing wealth for everyone seeking to flee.

Those subject to the tax could still seek to move wealth offshore secretively, and some would undoubtedly succeed. But they’ll be operating in an international landscape that is very different from the one that Europeans faced in the 1990s. The U.S. currently collects financial and tax information about both U.S. residents and expatriates from nearly all foreign banks under the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, enacted in 2010.

That kind of law would be unthinkable for any other country. But the United States, as the issuer of the world’s reserve currency as well as its top-rated borrower, has unique leverage to impose conditions and requirements on foreign financial institutions.

Nevertheless, the rest of the world followed suit with the Common Reporting Standard, a multilateral anti-tax evasion effort to collect the same basic financial information. The U.S. has yet to join the CRS, which has been a hurdle for foreign countries’ enforcement–but from the perspective of the U.S. IRS, all bases are covered.

For those who aren’t closely involved in international taxes, or who don’t have to deal with the patchwork of new rules personally, the magnitude of this sea change may be hard to grasp. Secret Swiss bank accounts used to be such a status symbol for the ultra-wealthy that they became a cliché. Now they’re no more. Countries that were well-known as tax havens are now signing up for information exchanges and transparency agreements. (Even Panama, infamous through the Panama Papers.)

There’s certainly been a lot of collateral damage, especially for U.S. expatriates or frequent travelers who now find that it’s nearly impossible to open new accounts at foreign banks. But in its central mission to do away with international tax secrecy, it’s largely been a success. The IRS now has so much global information, sorting through it is a significant administrative challenge.

It’s not that it’s impossible to hide money, either now or in a future with a U.S. wealth tax. Creative accountants could come up with hypothetical plans. (“So suppose you obtained secret loans against your stock, used it to buy valuable paintings, shipped those onto an island…”) But in the real world, not many wealthy people would be willing to take the risk. Bear in mind, it would already be illegal for the individual to hide this income abroad. What’s new is the number of financial tripwires their accountants or bankers would need to skip over, to avoid mandatory reporting requirements. They too would have to be willing to take the legal risk, and the kinds of financial institutions willing to engage in these kinds of behaviors are also the kinds that billionaires would be extremely reluctant to give control of their fortunes.

And the marquee billionaires–the Elon Musks, Mark Zuckerbergs and Jeff Bezoses–all have wealth that is held in stock, publicly traded on a transparent exchange. It would be impossible for them to hide their assets, without leaving a trail for tax authorities to follow.

Don’t get me wrong–implementing a wealth tax would still be a massive undertaking. Even if it were targeted at only the very wealthiest, it would require capacities that dwarf the current $80 billion enhancement at the IRS. The valuation challenges would be as difficult as enforcement of the current estate tax, but multiplied exponentially as they are undertaken on an annual basis.

But if Congress had the political will, it’s all theoretically possible. It would need to get over the constitutional hurdle first, however.

The U.S. Constitution only allows an income tax, enacted by the 16th Amendment, indirect taxes and direct taxes “apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers.”

Such apportionment is out of the question. It would require that the wealth tax be leveled at different rates for different states, which is not only unfair but would give taxpayers easy avenues for avoidance.

The constitution doesn’t offer much guidance on what a “direct tax” is, which has led to a lot of legal debate over the years. Courts decided that an income tax is direct, as it is levied on individuals, not based on transactions. Some have argued that this ruling was in error, but Congress seemingly confirmed it by enacting the 16th Amendment.

What we can be sure of is that at the time, a direct tax included a tax on land. That was more or less the point of the provision–a tricky way to block taxes on slave plantations. And since land was and is one of the key measures of wealth, it’s hard to escape the implication that a tax on assets is a direct tax as well.

Of course, there’s a lot of debate about this. But at the end of the day, does it really matter? Would Congress ever embark on such a massive new revenue measure, when its very validity is in question? And when there are other options available?

That may make a wealth tax all but impossible in the U.S., as a matter of policy. But it will continue to be a powerful political tool as a proposal. And it can move the discussion to other possible taxes, more modest than a wealth tax but still potentially radical steps from the status quo. Those include ending the stepped-up basis at death, hiking the estate tax, or enacting annual taxation of unrealized capital gains. All of those come with other potential pitfalls, but are potential ways to get at the massive wealth stockpiles that seem to separate the ultra-rich from everyone else.

That’s the essential policy point that has gotten more focus recently, the differences between our current taxes on income and taxes on assets. Recent works such as Prof. Dorothy Brown’s thought-provoking “The Whiteness of Wealth” have examined this issue from a societal and racial standpoint. Over the years, the tax system has become more and more accommodating to those that hold assets and property, than those who don’t. The basic cause is a concept that everyone, tax expert or not, can understand–people will always fight hardest to protect what they already have.

Dealing with that dynamic will require a huge degree of political will, and we saw a real-time demonstration of this as the Build Back Better and Inflation Reduction Act moved through Congress over the past two years. One by one, the measures that would have captured assets were removed, and lawmakers ultimately settled on new variations of income taxation.

The recent effort at the state level shows that the political momentum towards wealth taxation has not abated. The question is whether policymakers can navigate all of these hurdles to create a tax regime that effectively deals with the issue, without creating significant distortions.

DISCLAIMER: These views are the author's own, and do not reflect those of his current employer or any of its clients. Alex Parker is not an attorney or accountant, and none of this should be construed as tax advice.

LITTLE CAESARS: NEWS BITES FROM THE PAST WEEK

- The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development released on Thursday some long-awaited guidance on Pillar Two, or the 15% global minimum tax that nearly 140 countries agreed to in 2021. I'll have more to say about this in a bit--key points of interest here include the chapter on recognizing the U.S. tax on global intangible low-taxed income as a "blended controlled foreign corporation" regime, and a chapter describing how some common tax incentives will be protected under the plan. The U.S. Treasury Department said this ensures that low-income housing tax credits and the green energy credits enacted by the Inflation Reduction Act won't be adversely impacted by the policy, but no doubt the affected parties are pouring over the document now to find the devils in the details. Interestingly, the guidance doesn't include anything about how transferable tax credits will be treated, when that was seen as a major workaround for nonrefundable incentives.

- The OECD also released this week public comments for a recent discussion draft on Amount B, another part of its digitalization project that's expected to be crucial for developing countries. As expected, there's a lot of disagreement on the scope for Amount B. What also caught my eye--there doesn't seem to be much input from the developing countries themselves.

- One final release from the OECD, which was apparently in a rush to get things out by the end of January--a new manual on mutual agreement procedures and advance pricing agreements, which are both crucial to the functioning of the existing transfer pricing system. These will be all the more important as the world embarks on a global tax overhaul that's sure to create a lot of uncertainty in the near-term.

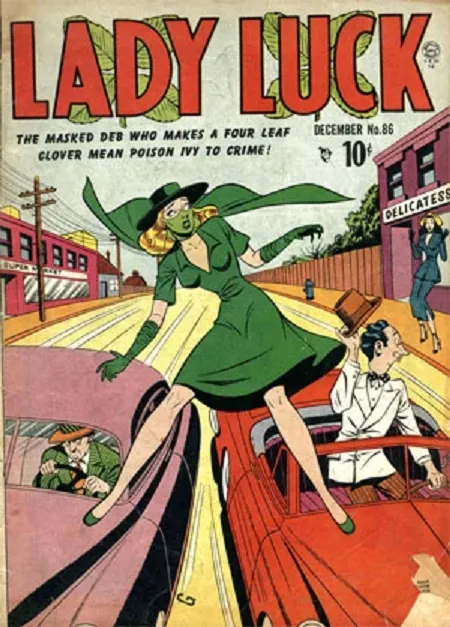

PUBLIC DOMAIN SUPERHERO OF THE WEEK

Lady Luck, first appearing in The Spirit comic strip in 1940. Brenda Banks, bored with the socialite life, becomes a "modern lady Robin Hood" and world traveler to fight crime in disguise.

Contact the author at amparkerdc@gmail.com.