Luck of the Irish

Why is the Emerald Isle doing so well in the post-BEPS world, and what does that mean for the overall global tax landscape?

Twenty years ago this summer, I made my first and only trip to Ireland. A dim U.S. college kid doing the Eurail thing after his mandatory semester abroad, I arrived in Dublin, drank my way to Galway, and ended up spending a day on Inishmaan, one of the three Aran Islands on the western coast.

I knew that Inishmaan was the least-populated and least-visited of the islands, but I wasn’t quite prepared for how desolate it would be. There was a general store, a few modern wind turbines, a pub with Guinness (of course) and an endless maze of stone fences. Most of the signs were (and I believe still are) in Gaelic, not English. I’m not sure when electricity made its way to Inishmaan but it felt like it couldn’t have been longer than a decade ago.

That sense of the past and present living together is a big part of what attracts people from around the globe to Ireland, I think. Weirdly enough, it’s also something I think about when I read about their tax revenue.

The tale of Ireland’s economic turnaround–the “Celtic Tiger”–from one of Europe’s poorer countries to a continental tech hub is at this point well-known. Whether tax benefits were the primary driver or just a contributing factor is still hotly debated. Companies saw the chance to maneuver profits it earned elsewhere into Ireland through arrangements with valuable intangible assets like patents. Eventually, those on-paper structures turned into real regional headquarters.

People remember the colorful terms relating to its perceived status as a tax haven–the Double Irish, “Leprechaun Economics.” Ireland invented the patent box and is still under harsh examination by the European Commission.

But clearly, its days as a “classic” tax haven are long gone. It’s no longer a small, poor island with little to offer but a low tax rate and a mailbox. (If it ever was.) Ireland’s tech workforce is thriving and well-educated, and Dublin is home to countless real research and development facilities. Post-Brexit, it’s the only English-speaking nation in the European Union.

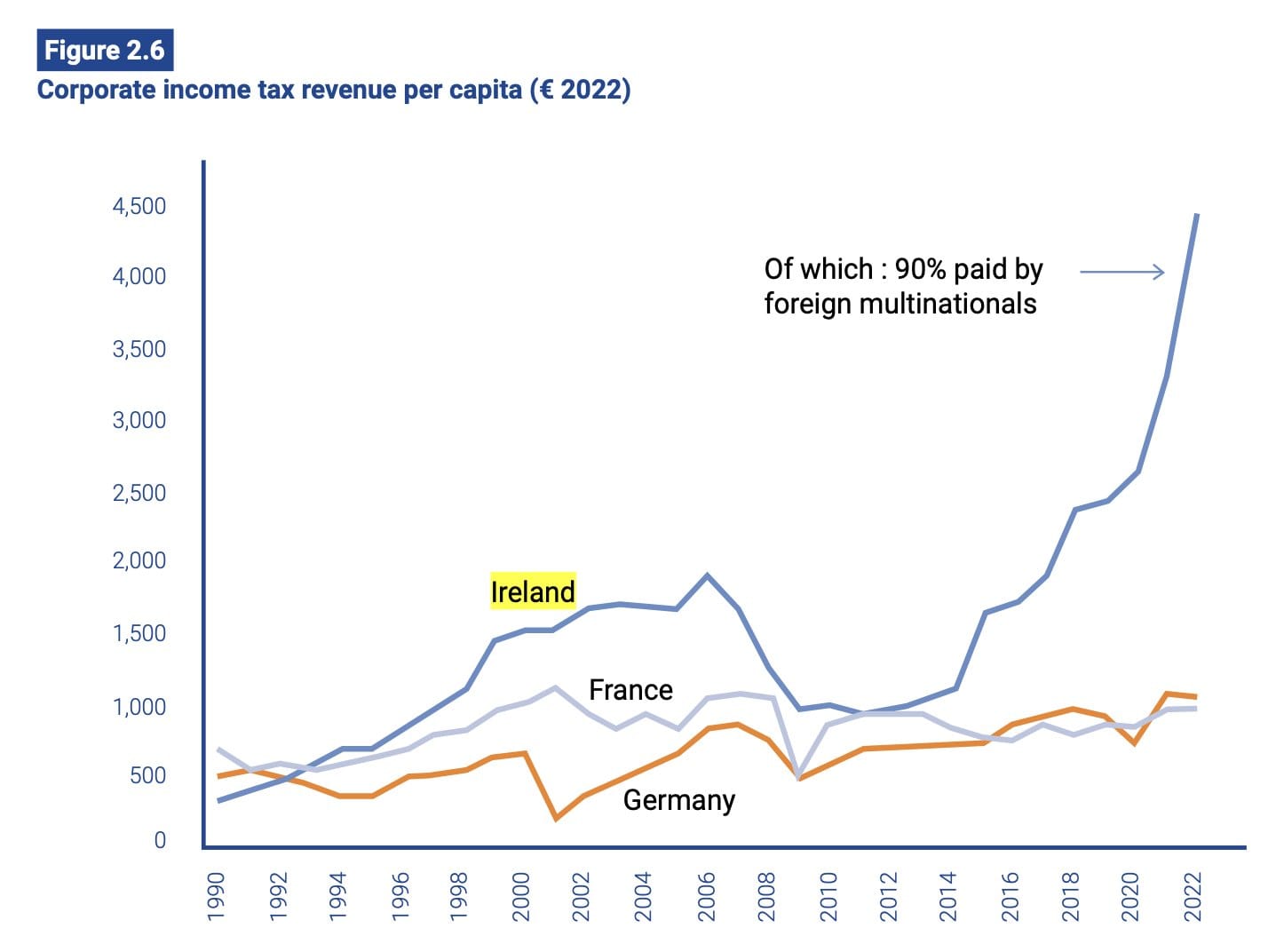

So perhaps it’s not too surprising that the country’s tax revenue continues to go up, despite international efforts to clamp down on the very practices that Ireland pioneered and came to be identified with. A recent report from the European Tax Observatory, a think tank sponsored by the EC, singled out Ireland and the Netherlands as jurisdictions which received $140 billion in shifted profits in “recent years.” According to a chart from the report, Ireland's per-capita corporate income has increased exponentially in the years since it closed off the infamous Double Irish structure, and since the reforms from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act took effect.

You could use this as evidence that those reforms aren’t working–income is still being shifted and it’s still chasing the lowest rates. Ireland, with a 12.5% headline corporate tax rate plus a 6.25% "knowledge development box" for intangible income, is still an enticing jurisdiction.

Or, you could argue that it’s actually evidence that the reforms are working. The income isn’t only chasing rates but also workforce and economic substance, just as the rules say it should. Income is finally being paired with value generation. (And, needless to say, all this revenue shows that taxes are being paid.)

That Ireland could have been so well-positioned under both the old regime and the new regime can be a little hard to wrap your head around. One thing to remember is that Ireland used to act more as a gateway than a destination. Non-Irish companies would use the country and its tax treaties (and generous tax rulings) to set up Irish subsidiaries with branches in low or no-tax jurisdictions. (That’s where the “double” of the Double Irish comes from.) Ireland was happy to supply this trip free of charge, because the traffic created so many knock-on benefits for its economy. If you want to stick with the leprechaun metaphor, Ireland was the leprechaun but the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow was in the Cayman Islands or Bermuda.

But those days are done. Ireland changed its branch allocation rules to no longer allow the dual structures that enabled the Double Irish or one of its variations. The OECD’s “DEMPE” rules cast doubt on structures that allocate income associated with intangible assets to jurisdictions without the capabilities for “development, enhancement, maintenance, protection and exploitation” of them. And rules like the TCJA’s tax on global intangible low-taxed income and the OECD’s Pillar Two global minimum tax are meant to target countries with high profits and few employees or assets.

Ironically, considering how hard Ireland fought against the Pillar Two rules, the new regime has changed it from a gateway to a destination. That income that may have been in the Caribbean is, in many instances, flowing towards Ireland.

A crucial point is that while the new rules put a premium on workforce and tangible assets, they don’t necessarily require income to be matched to the exact facility or employee that generated it. Transfer pricing rules are supposed to do that, but if they worked all the time we wouldn’t need all of these additional protections. In an age where a smartphone can require more than 200 patents and a new drug spends decades in development, who can possibly say which scientist in which lab was responsible for what percent of a company’s annual profit?

A comparatively rougher calculation of payroll and assets may be much more imprecise, but at least it’s administrable and puts a ceiling on profit-shifting. Or at least, that’s the thinking.

Even the modified nexus standard used by the OECD to determine harmful tax practices–created in response to the kind of patent boxes that Ireland was so infamous for–allows for some hedging. These are the standards that a country must enforce to offer special tax rates to intangibles, without being considered out of compliance. According to the OECD, the standard uses research expenditures as a “proxy” for value creation–so long as the expenditures are “directly related to development activities that demonstrates real value added by the taxpayer.” It’s a much more factual approach than the hard-and-fast formulas of Pillar Two, but it still acknowledges some blurriness between the facilities and the income.

I don’t really mean to focus so much on Ireland, I’m trying to make a point about the overall system. Ireland’s success is emblematic of overall trends in international taxation.

But two factors could completely upend this new paradigm–the rise of highly valuable workers, and the rise of mobile work.

To go back to that scientist working in the lab–despite what I said, sometimes he or she may well be responsible for a huge amount of income. It’s yet another aspect of today’s knowledge economy. Can these new rules distinguish between a small team of lawyers collecting mobile income on paper and a small team of programmers who’ve invented the next social media app sensation?

And will that team even be centered in one location? Since the coronavirus pandemic, remote work has turned from an occasional perk to a ubiquitous reality. Offices and headquarters still matter, but it seems like they matter slightly less every day. As Aitor Navarro wrote in an interesting new paper for the Max Planck Institute for Tax Law and Public Finance, this new reality could undermine the very premise of substance-based requirements.

Just as these rules adapted to the modern economy are put in place, the ever-changing nature of that economy could shake them from their moorings yet again.

DISCLAIMER: These views are the author's own, and do not reflect those of his current employer or any of its clients. Alex Parker is not an attorney or accountant, and none of this should be construed as tax advice.

A message from RoyaltyStat:

RoyaltyStat® is the market leader in databases of royalty rates and service fees from third-party transactions to facilitate transfer pricing compliance and the valuation of intangibles. Our focus on high-quality data, unique transfer pricing analytics, and knowledge-based customer support makes us the choice of transfer pricing practitioners worldwide, including the top accounting and law firms, Fortune 500 multinational entities and more than 15 tax administrations. Find out more at royaltystat.com.

Thank you for reading! If you are reading this without a subscription, you can sign up here at no cost to receive weekly emails and access to past articles on my website.

LITTLE CAESARS: NEWS BITES FROM THE PAST WEEK

- Monday was the U.S. Treasury Department's deadline to submit comments on the text of the OECD's "Multilateral Convention" to implement Pillar One, the new customer-based taxing right that's meant to complement Pillar Two. Comments from taxpayer groups are beginning to trickle out. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the Tax Foundation, and the National Foreign Trade Council all released their comment letters, which expressed various concerns with the proposed treaty. (That's still seen as a long-shot to ever being in effect, but in tax policy you never know.) One big common issue is how the treaty would identify impermissible digital services taxes, with the groups worried that countries will find ways to work around their requirements and continue to target U.S. tech companies with new levies.

- Treasury also released new proposed guidance on whether some of the Pillar Two taxes are eligible for a foreign tax credit. While the income inclusion rule, Pillar Two's primary tax, generally isn't creditable, in some cases foreign subsidiaries that operate as regional headquarters could receive a credit. The department said it is still analyzing whether the under-taxed profits rule–the rule that's U.S. corps are really worried about–although few believe it will end up being creditable. As Pillar Two critics keep noting, the UTPR seems well out of step with traditional notions of income taxation.

- Speaking of the OECD's work on harmful tax practices, the organization issued a report on the results of peer reviews for jurisdictional exchange of information on tax rulings for 2022. It found that 100 countries are in compliance, including the United States. For what it's worth, Ireland is in compliance too, while Switzerland–another reputed haven that has supposedly turned over a new leaf–was chided for exchange delays.

PUBLIC DOMAIN SUPERHERO OF THE WEEK

Every week, a new character from the Golden Age of Superheroes who's fallen out of use.

The Flame, first appearing in Wonderworld Comics #3 in 1939. After washing ashore a Tibetan monastery as a baby after a flood (huh?), Gary Preston was raised by the monks and tutored in their mystical powers. He can control fire and heat, melting bullets and appearing at will from any fire source. His weakness is, you guessed it, water.

Contact the author at amparkerdc@gmail.com.