Yes We CAMT

Republicans haven't put Biden's 15% corporate minimum tax in their sights yet. Is it just a matter of time, or does it actually have some bipartisan appeal?

Missouri Republican Rep. Jason Smith beat out Rep. Vern Buchanan, R-Fla., the party favorite, to become chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee in January. And in the short time since then, he’s made it clear he won’t be a typical Republican committee chair.

As the primary tax-writing committee in the House, Ways and Means normally attracts a certain brand of down-to-business conservative. Smith, though, has already spooked corporate America with his Trump-style rhetoric.

With his comb-over, black-rimmed glasses and nasally voice, he may seem like a real estate lawyer–and he is one–but his speeches show that he’s part of the new wave of post-Trump Republican firebrands. Heavy on populism, light on traditional libertarian priorities, and not always favorable to big business.

He’s already held two “field hearings” outside D.C. to emphasize what he claims is economic stagnation in the heartland due to Biden administration policies. Rep. Richard Neal, D-Mass., the committee’s ranking member, managed to keep cordial relations with past Republican chairmen, even during the heat of the controversial Tax Cuts and Jobs Act passage. But he claims that Smith’s staff has stepped up to a new level of partisanship, using routine matters for messaging and stonewalling the other party.

And in outlining the committee’s priorities for the upcoming two years, he said it would consider whether to “continue showering tax benefits on corporations that have shed their American identity”--not exactly an encouraging phrase for multinationals.

One other interesting way that Smith’s priorities likely diverge from business interests is his indifference to the Inflation Reduction Act’s corporate taxes, especially the 15% corporate "book" alternative minimum tax. He doesn’t support it, of course, but he’s let it be known that he doesn’t see repealing the CAMT to be a goal worth spending time or energy on.

"The book tax may be the most vocal thing that you hear in Washington, D.C. because there's a lot of high-paid lobbyists and folks that are pushing it because they don't like what just happened, but that's going to be in the back of the line in the priorities," Smith said during an interview with Punchbowl News in December 2022, before he was elected to the chairmanship.

Smith said policies that "will provide for more jobs, wage growth, financial security, that will help American workers, families and farmers" would take priority over repealing the book minimum tax.

There's also hardly any mention of it in his speeches–but plenty of ire focused on the $80 billion increase in Internal Revenue Service funding and the administration’s 15% global tax agreement at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

In the Trumpian GOP, that makes sense. A supposed army of new IRS agents looking to invade the financial privacy of millions of ordinary Americans and small business owners (despite the administration’s assurances that they wouldn’t) feels vivid and immediate. And the OECD agreement smacks of multilateralism and a failure to put America first, with the added specter of Chinese influence.

By comparison, the 15% corporate minimum tax feels abstract and unconcerning to ordinary voters. And, perhaps, sensible as well–even Republicans don’t disagree with the idea that wealthy corporations ought to “pay what they owe,” as Biden claims the new tax will accomplish.

In this, Smith may not be alone. While many Republicans have declared their opposition to the CAMT, and there is a bill to repeal it, that hasn’t become a major priority for House Speaker Kevin McCarthy or the GOP leadership, either. It wasn't included in H.R. 1, the new majority's first legislative initiative, or its proposal to increase the debt limit.

Is it possible that Republicans have found a tax they can live with?

If so, that would be ironic, because there are plenty of centrist and even left-leaning commenters who’ve criticized the tax.

Howard Gleckman, a senior fellow at the Tax Policy Center, which is co-managed by the Brookings Institution, said the tax “creates a mess of policy and administrative problems.”

Mark Mazur, a former U.S. Treasury Department official in both the Obama and Biden administrations, conceded that it was “not the best policy,” noting that it would be better if Congress fine-tuned the tax code itself, rather than creating a secondary minimum tax backstop.

And the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants outlined dozens of potential problems with the implementation in the tax. Treasury could use its broad authority to fix those with tweaks, but that raises questions about whether it’s appropriate for the executive branch to have so much control over the tax code, a constitutional responsibility of Congress.

With all this, it's clear there's plenty that Congress could pick over in the tax and make trouble for the Biden Administration. If it was so inclined.

CAMT targets companies which report an effective tax rate lower than 15%, using the financial accounting data–for instance, what’s reported to stockholders–as the tax base, rather than the income code. Critics claim this is problematic because financial accounting rules have a basic purpose that’s different from defining the tax code, and mismatches don’t necessarily indicate avoidance. Furthermore, often these divergences are due to incentives that Congress has enacted–if that’s bad, why not just repeal them?

Indeed, Congress ultimately carved out many exceptions to CAMT, leaving it as an ungainly and amorphous regime.

But however complex or contradictory the idea is in practice, in political rhetoric it has a simplicity and intuitiveness which has made it politically powerful. Making corporations pay what they ought to in taxes–what’s wrong with that? This is surely why Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., if nothing else a canny reader of public moods, opted to keep CAMT while nixing the 15% global minimum tax agreement. A pact with foreign nations to keep taxes from going too low likely sounds ominous to many Americans. Whereas a minimum tax for companies that achieve a low effective tax rate sounds like something that we ought to have been doing anyways.

This basic dynamic dashes the hopes of some in the corporate world that the CAMT could prove to be a short-lived regime. Congress enacted a similar minimum tax in 1986, but then allowed an unceremonious death three years later, with few mourning its passing. It was replaced by a more standard AMT, which lasted for decades but was repealed without much debate in 2017.

For corporate America, this could mean that opposing CAMT makes less sense than learning how to adapt to it. Are there ways that the tax could be tweaked to make it more reasonable?

(Every once in a while I’ll hear someone express hopes that it could be made compliant with the OECD agreement, perhaps as a Qualified Domestic Minimum Top-Up Tax. But I don’t ever see that happening. The taxes are too different, and trying to change CAMT runs into same problems that prevented enactment of the agreement in the U.S. in the first place.)

You’d think that one bright side of CAMT is that companies at least wouldn’t need to deal with the PR headaches when mainstream media reports on low effective tax rates. But with so many exceptions written into the law, it’s likely that many companies will still have low ETRs, despite the CAMT. That may take years to become clear, but when it does Biden and the Democrats may have some explaining to do.

The basic political power of the CAMT may cause some blowback in the other direction as well.

DISCLAIMER: These views are the author's own, and do not reflect those of his current employer or any of its clients. Alex Parker is not an attorney or accountant, and none of this should be construed as tax advice.

LITTLE CAESARS: NEWS BITES FROM THE PAST WEEK

- Nigeria was one of a handful of countries that declined to support the OECD agreement when it was first announced in 2021. And they still don't support it--but on April 13 they did announce that they had met with OECD officials and had decided "to commence immediate implementation of fiscal policy measures around the Global Minimum Tax Rules, in view of the fact that other jurisdictions around the world have commenced implementation of measures that will enable them to reap top-up taxes allowed under the rules, which will be to the detriment of Nigeria." This follows an announcement from Kenya, another holdout, that it was repealing its digital services tax, which is a key conflict with the new OECD standards. Amid a hearty debate about whether OECD tax projects are addressing the needs of developing countries, these are intriguing developmnets. If nothing else, they demonstrate how much pressure smaller, poorer countries are under to follow global norms.

- The Republican leadership in the U.S. House of Representatives finally unveiled a plan to raise the U.S. debt limit, along with significant limits on federal spending and a rollback of most of the energy credits that were enacted last year in the Inflation Reduction Act. This is not expected to pass the Democratic-controlled Senate, but could be the starting point for negotiations over how to raise the limit. (Which must be raised, somehow, to avoid default and a global economic meltdown.) The plan doesn't touch many international items, but it does call for the rollback most of the new funding for the IRS enacted last year, some of which would have gone towards heightened enforcement against international tax evasion. It's unlikely that Biden would ever compromise on what he views as one of his signature accomplishments, but for now it's on the table.

- Speaking of smaller developing countries and the OECD, the organization announced that Mongolia has agreed to implement the automatic exchange of financial information, part of the transformative new anti-tax evasion network. This follows an announcement from last week that Zimbabwe was joining the Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes, which oversees the system. (Mongolia was already a member.) This exchange comprises most of the world now, and is another sign of OECD progress outside of the Two-Pillar project.

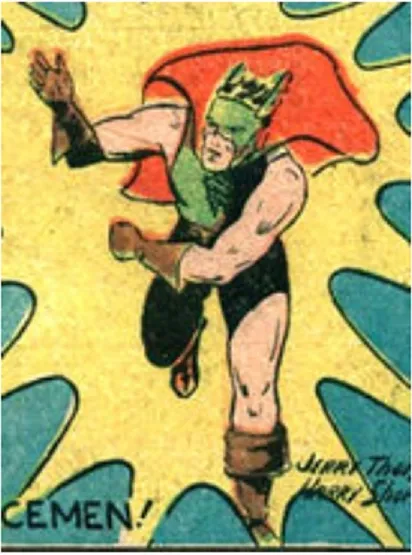

PUBLIC DOMAIN SUPERHERO OF THE WEEK

Bob Phantom, appearing first in Blue Ribbon Comics #2 in 1939. Walt Whitney, an incisive and controversial columnist and radio announcer (likely based on Walter Winchell), derides the police daily for their ineffectiveness. But secretly, he aides the fight against crime as Bob Phantom, with super-strength and the apparent ability to disappear and reappear at will. At least some of these powers come from a magician mentor who also supplied the name, but the rest is apparently a mystery.