Don't Do the (Tax) Time Warp Again

As in 2017, Congress faces a major overhaul of the tax code in the upcoming year. But if lawmakers think offshore cash can help cover the costs, like with the TCJA, they could be in for a shock.

It’s election season in the United States, and Donald Trump is running for president. His opponent is a well-qualified woman who has struggled to connect with voters in the past–but is currently leading him in the polls. The Middle East remains a tinderbox and Americans are dissatisfied with the current state of the economy, even as normal indicators show continuous economic growth.

Is it 2024 or 2016? Sometimes it’s hard to tell.

Many commented on how the COVID pandemic seemed to break down our conventional perceptions of time. A hell of a lot has happened in the past 8 years, and in some ways life from 2015 or earlier feels like a different, unfathomable world. In other ways, it feels like it was barely yesterday. It’s all a jumble.

What’s true for the world at large is true for tax policy as well. A lot has happened in the tax world in the past 10 years–arguably, the most pivotal decade ever for the global tax system, or at least the most important since it was created in the 1920s. And yet, a lot of the rhetoric has been slow to catch up to rapidly changing systems and dynamics.

Whatever happens in the next two months–which is also likely to feel like an eternity as well as a blink of the eye, paradoxically–Congress will face a monumental task in 2025. Huge portions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act are set to expire or change that year, as part of the triggers and sunsets that lawmakers included in the legislation to fit its mandated revenue score. Allowing all of these changes to go into effect would likely be unacceptable to either political party, so unless one of them has the presidency and a strong majority of Congress–unlikely, but not unthinkable–a deal will have to be in the offing.

This deal probably won’t just include the policies affected by the TCJA triggers. Those will be part of it, but the stark math and politics will likely force negotiators to look at the tax code as a whole. Democrats will want to use the expiration as a lever to push for their prized priorities, such as expanding tax credits for low-income Americans. Republicans will want to extend as much of the TCJA as possible, and Trump has promised to push down the corporate tax rate even further. (The 21% corporate rate itself is permanent and won’t change in 2025, but many other provisions affecting corporations are at play. By and large, the TCJA expirations mostly affect individuals.)

Then you have tax issues that don’t exactly cut across partisan lines–like the limit on the deduction for state and local taxes, which both Democrats and Republicans from wealthier states like New York and California have blasted as unfair discrimination.

Extending the TCJA wholesale could cost as much as $5 trillion over the next ten years. Both parties will be looking for new revenue to help cover their agenda items and make them more politically acceptable.

This is where the time warp comes in. Sometimes, I’ll hear people talk like it’s 2016, and there are still trillions of dollars offshore held by U.S. corporations just waiting to be brought home, enough to fund a huge chunk of these priorities. Since international tax reform was one of the items that got left on the cutting room floor in the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act negotiations, many assume that implementing the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Pillar Two global minimum tax, or other big international changes, could be a significant piece in the 2025 puzzle.

It could be. But it’s not nearly as clear as it was in 2016. The amount of public data we have about foreign income is still infuriatingly low, enough that economists are able to draw widely different conclusions about what’s out there. And because of that, people need to know that bringing foreign dollars home is not going to be a steady, reliable revenue source to cover what will need to be covered. While public narratives about tax avoidance often still imply that companies are still shifting huge portions of their profits to offshore tax havens, the situation is a lot more fluid and less certain than it was in 2016, when the ability to defer foreign income left mountains of earnings overseas.

In fact, there is still trillions being kept offshore. But the question is, why? Is it solely to take advantage of lower tax rates? (And if so, is that being done by separating income from the economic activities that generated it, wherever those are–a subtle but very crucial distinction.) Is it being held for regulatory reasons, or other advantages that are outside the tax realm? Or is it just lethargy–in the post-BEPS, post-TCJA, and post-pre-Pillar Two world, companies aren’t sure where to move it, so they just leave it where it is for the time being even if it’s no longer as profitable to do so?

It’s probably a mix of all three. (With the last one a major factor, at least anecdotally.) It all matters in terms of how much the U.S. can expect to grab through changes to its international tax rules. If a certain structure is no longer tax-advantageous to a corporation, getting them to unwind it won’t necessarily create an influx of new revenue for the U.S. It could be offset by canceling a cost-sharing arrangement that included payments to the U.S., or revenue from the tax on global intangible low-taxed income. Or, it could be that the company responds by moving the money to another, less-tax-favored jurisdiction, which is perhaps an improvement in terms of overall global policy but won’t help the U.S. Treasury much.

This is all estimated on a ten-year timeframe, even if it’s to offset immediate costs. At the risk of going on about time again, you have to think fourth-dimensionally.

As I’ve said before, so much comes down to the question, is the TCJA working? Even as we approach its expiration date, the answer is still unclear. Or as UCLA economics professor (and former Treasury deputy assistant secretary) Kim Clausing put it in a recent paper, the law’s international tax provisions had “potentially ambiguous effects on incentives for offshoring and profit shifting.”

One dynamic I suspect is a big factor here is that companies are reporting more income in the U.S. due to these changes–but that income is being wiped out by the R&D credit, and other generous subsidies in the TCJA. Those are generally popular and have significant political support, so wringing revenue from these corporations will harder than making offshore changes. We may end up fixing the wrong end of the equation.

The TCJA tried to stem offshore tax avoidance through the GILTI tax, which is imposed on the foreign earnings of U.S. companies, if they are being taxed by other jurisdictions at less than 10.5%. GILTI only applies to “intangible” earnings, through a formula based on the amount of tangible property held offshore. GILTI is applied on an aggregate basis, so it blends all foreign earnings before applying the 10.5% test.

Pillar Two works in a similar way to the GILTI tax. But one key difference is that it applies on a country-by-country basis. Even before Pillar Two was unveiled, Democrats keyed in on this design choice, claiming that it renders GILTI toothless because base erosion can still occur, so long as there’s enough income earned in higher-tax jurisdictions to average it out. Republican tax-writers claimed that the blending gave companies some flexibility and eased administrative costs, while still blocking the overall incentive for tax avoidance by giving it a floor.

I tend to focus on this issue, because if profit-shifting is still happening in the post-TCJA system, it would largely have to be happening through this alleged loophole. So was the barn door left open? Or does GILTI pretty much do its job, not eliminating base erosion entirely but reducing it to a degree that it’s no longer a significant incentive for U.S. corporations?

Here are some of the hints we’ve gotten about this question. Probably the most “authoritative” estimate is the Joint Committee on Taxation’s score for the Build Back Better Act, which included several international tax changes. According to JCT, the provision to convert GILTI into a country-by-country system (not including the increase in the rate) would raise $57 billion over ten years. In fact, it’s not even that much, as the estimate also includes how much would be raised by eliminating GILTI’s substance-based carveout, the qualified business asset investment.

Since then, JCT issued a score for Pillar Two–which found that it could raise as much as $224 billion, or lose up to $175 billion over 10 years. Oy vey.

To drill down into that a bit more, JCT scoped out several scenarios for baseline assumptions. Since other countries have already moved ahead in implementing Pillar Two, those are the baselines to really focus on. Taking worldwide enactment as a given, the estimate shows that the U.S. would raise $66 billion more by passing Pillar Two, than not passing it. (While still losing money overall, compared to a world without Pillar Two.) Another interesting data point–in a theoretical world where no other countries enacted Pillar Two, the U.S. could raise $103 billion by passing the income inclusion rule, Pillar Two’s equivalent to the GILTI tax.

Then there’s the administration’s own numbers. In 2023, Treasury said that enacting the CBC change with GILTI–along with many other international tax changes–could raise $493 billion in a decade. For the same provisions, the budget request released in 2024 showed that the same provision would raise $374 billion. Testifying before the Senate Finance Committee, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen said the difference was largely due to other countries’ enactment of Pillar Two, reducing the size of the revenue pool. This is an interesting point, because it hints at a key dynamic–much of this income may have been shifted, but it could have been shifted from foreign jurisdictions, not the United States. So while it’s good to see it back to where it belongs, it won’t create more U.S. revenue, at least directly.

There are estimates from private organizations as well. The well-respected Penn Wharton Budget Model predicts that Biden’s proposed international tax changes–which includes the GILTI tweak as well as many others–would raise $317 billion. The conservative-leaning Tax Foundation puts the number at $271 billion.

Given all of these competing figures, I think it can be generously stated that making the CBC change to GILTI would raise around $100 billion, give or take. That’s a lot of money. But this is in the backdrop of trillions of dollars in tax changes. It’s maybe not a drop in a bucket, but it’s not much larger than a teacup.

Congress could probably raise more by repealing the FDII deduction, another major Biden proposal. That’s a big topic I should probably devote another newsletter to, but while it’s maybe an over-generous tax benefit to Silicon Valley, it’s not exactly an example of income-shifting either. And Silicon Valley is sure to fight back.

Ultimately, JCT will put out a number on this, and that will be the number that Congress has to use, at least if they follow long-held custom. All of the rest of this is more about affecting rhetoric and public discussions, which are going to need to adapt to a very different world.

DISCLAIMER: These views are the author's own, and do not reflect those of his current employer or any of its clients. Alex Parker is not an attorney or accountant, and none of this should be construed as tax advice.

A message from Exactera:

At Exactera, we believe that tax compliance is more than just obligatory documentation. Approached strategically, compliance can be an ongoing tool that reveals valuable insights about a business’ performance. Our AI-driven transfer pricing software, revolutionary income tax provision solution, and R&D tax credit services empower tax professionals to go beyond mere data gathering and number crunching. Our analytics home in on how a company’s tax position impacts the bottom line. Tax departments that embrace our technology become a value-add part of the business. At Exactera, we turn tax data into business intelligence. Unleash the power of compliance. See how at exactera.com

Sign up for the Emperor Subscription

Thanks for reading! Don’t forget, you can sign up here for a paid Emperor Subscription, to get extra bonus content, including interviews with newsmakers in the tax field and deep dives on various international tax topics.

This Friday, I look into the history of the U.S. foreign tax credit.

The Emperor Subscription will also give you access to past content, such as interviews with former OECD tax chief Pascal Saint-Amans, Tax Foundation CEO Daniel Bunn, and former U.S. Treasury official Jason Yen.

The transactions are handled by Stripe, a safe and secure payment processing platform. Electronic receipt and invoice available. (If anyone has any difficulties subscribing, please let me know.)

You can sign up here for $8/month or an $80 annual payment. Please consider subscribing!

LITTLE CAESARS: NEWS BITES FROM THE PAST WEEK

- As I mentioned earlier, it’s campaign season here in the U.S., and the election results will be pivotal for deciding the future direction of the U.S. tax code. The Democratic nominee, Vice President Kamala Harris, hasn’t issued much in the way of details about her tax plans–but since she only entered the race a month ago, that’s somewhat understandable. However, her campaign has indicated that she supports the proposals in the Biden Administration’s latest budget request. In theory, this means she supports a slew of international tax provisions–not just Pillar Two implementation, but limiting corporate inversions, expanding the prohibitions on hybrid mismatch arrangements and the deductibility of interest, and many other small and big changes. Whether this would mean a Harris Administration would aggressively push for these items is another matter. The details of tax policy are often hammered out by the tax-writing committees of Congress anyways. A president's role is normally to affect the overall direction. In that sense, Harris has continued Biden’s focus on raising taxes for the richest Americans and large corporations, a continuation of the Bidenomics philosophy that sometimes can create more contradictions than its supporters presume.

- The OECD’s Forum on Harmful Tax Practices released determinations for six jurisdictions’ tax regimes, finding that all but one (Croatia’s investment promotion credit) met their standards for acceptable tax benefits. Croatia’s remains under review. Probably the biggest item is Hong Kong’s “profits tax concession for aircraft lessors and aircraft leasing managers,” which is considered grandfathered under the FHTP rules and has been deemed non-harmful.

- There’s usually a third item, but in the late days of August these can be hard to find. Enjoy the rest of your summer and get ready for an eventful fall!

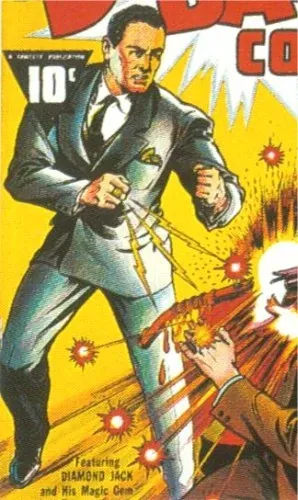

PUBLIC DOMAIN SUPERHERO OF THE WEEK

Every week, a new character from the Golden Age of Superheroes who's fallen out of use.

Diamond Jack, first appearing in Slam Bang Comics #1 in 1940. Given an ancient mystical diamond ring by a magician, Jack possesses nearly limitless powers, which he uses to fight crime, apparently in a smart-looking suit. A dapper gent with a dapper name.

Contact the author at amparkerdc@gmail.com.